Can technology make tourism more transformative ?

Transformative tourism (TT) is a type of meaningful and purposeful tourism. Traditional tourism is often used as an escape mechanism from everyday life (5). Transformative tourism is motivated by seeking (10). In transformational tourism the tourist seeks personal growth during their travels, which can take place in areas such as well-being, spirituality and education. The […]

Is smart tourism better tourism?

Nowadays, Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) are omnipresent. The digital age and its innovations in ICTs have changed society as well as economic and environmental development profoundly. ICT innovations are perceived and identified as one of the crucial game-changers in reaching Sustainable Development Goals.1 In this context, “smart” has become a buzzword. Gretzel, Sigala, Xiang […]

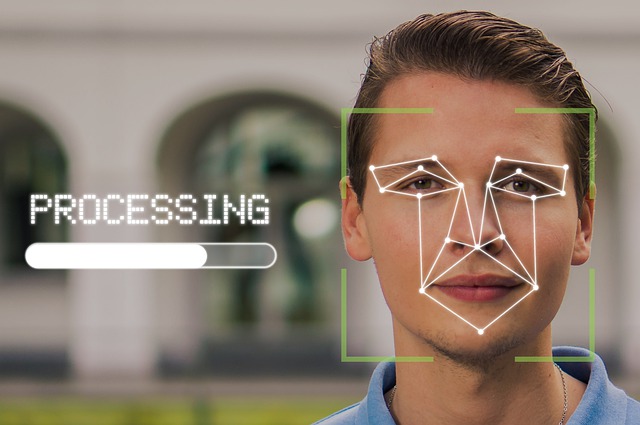

Facial recognition systems – the key to a more seamless future of tourism services?

Biometric systems are becoming a more mundane part of our everyday lives. We use for example our fingerprints and facial recognition systems to unlock our devices, to make mobile payments and to pass the border control routines at airports. These technologies are developing all the time, making them more accurate and simpler to use, pervading […]

Why should Smart Tourism Destinations invest in IoT solutions – or should they?

In recent years, the tourism industry has embraced the idea of Smart Tourism Destinations, emerging from the concept of Smart Cities. In both, the beating heart is the marketing word ‘smart’, representing all things that can be embedded or enhanced by technology¹. In fact, technologies such as cloud computing and the Internet of Things (IoT), […]

Digital Tourism Think Tank 2019 – Day 1

#DTTT 2019 What did I learn? I had a great possibility to participate in Digital Tourism Think Tank Global 2019 on 4rd and 5th of December, which this year took place in Espoo. DTTT Global is, in my opinion, one of the most interesting conferences as it gathers a bunch of tourism DMO’s and […]